Opinion Piece: The Trouble With Loot Boxes

-

Updated: 14th Aug 2024

Video game loot boxes have been in the news yet again after being linked to problem gambling last year . This time the children’s commissioner for England wants them classified as gambling and a maximum daily spend limit imposed. The UK is not the only country with concerns – in Belgium, for instance, video gaming companies have been banned from selling loot boxes for real money. But are loot boxes really gambling and would banning them solve anything?

WARNING: Extremely long opinionated rant follows!

- The Loot Box Controversy

- Loot Boxes Are Not Just Online

- The Problem With Scratchcards

- The Normalisation Of Gambling

- Ban? Or Educate And Regulate?

- How To Regulate?

- What Else Can Parents Do?

The Loot Box Controversy

A loot box is an item in a video game that can be bought with in-game currency purchased with real cash (or sometimes collected via prolonged play). After paying for or otherwise claiming the loot box, the player is able to open it and only then are the contents revealed. As loot boxes contain items that can be used for in-game purposes only and are not redeemable for cash, they are not classed as gambling for regulatory purposes. The big question is, should they be? Are they really so very different to the bonus games that are often found at online bingo sites, where players spin the wheel to find ut what they have won?

The outrage over loot boxes really started with their appearance in Star Wars Battlefront 2 in 2017. Most players were already familiar with loot boxes from other popular MMOs (massively multiplayer online games), but in games such as Overwatch the items in the loot boxes were cosmetic enhancements rather than being essential to the gameplay, and loot boxes could be collected (slowly) via prolonged play as well as being purchasable with real cash. In Star Wars Battlefront 2, on the other hand, the game was widely considered to be pretty much unplayable without buying loot boxes and it comes as no surprise that many players were angered by this.

In fact, loot boxes in online games have been around ever since MMOs started to move from the subscription model to the freemium model in reponse to the availability of in game purchase via Facebook, the AppStore and platforms such as Steam. Games like Farmville and Candy Crush were free to play but made it super easy to buy power ups and premium items in the middle of a game; in these games, at least you did know exactly what you were getting for your money.

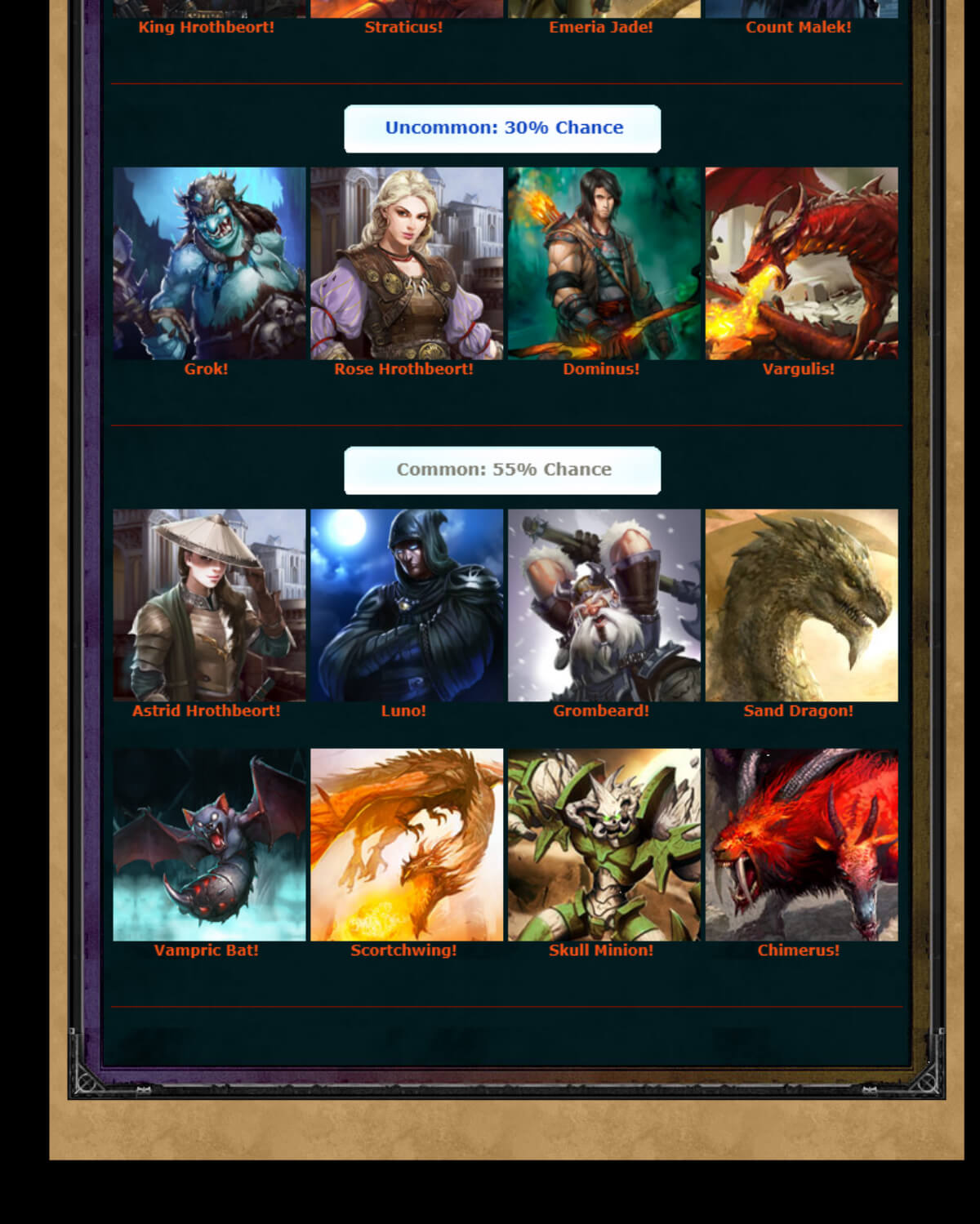

My first encounter personally with online loot boxes was in 2009 in the fantasy MMO Castle Age, available on Facebook and Apple devices (with a age rating of 9+ in the AppStore). The content of the game in general has absolutely nothing to do with casinos, betting or gambling, but there is an option to roll mystery chests to obtain premium items. The in-game currency needed to buy a mystery chest can be collected via gameplay (a long and laborious process) or bought with real money – in which case each roll ends up costing around £4. They also give away free rolls from time to time as prizes in in-game events.

Castle Age was and still remains far ahead of its time in that it shows the odds of getting the various items in the chests. Most games that have loot boxes don’t give the odds – they just classify prizes as common, rare, super rare etc without explaining what that means. I personally happen to think this is absolutely outrageous and can’t understand why they are allowed to get away with that under consumer law or why anyone would buy a box without knowing the odds – but as we will see later, this isn’t a widely held point of view.

What I soon noticed about the mystery chests was that even though the odds were clearly stated players consistently misinterpreted them. The chance of getting an epic general from a chest is 5% and most players seemed to think that meant that if they bought 20 rolls they would be bound to get one (though not necessarily the right one as there are 4 different ones in each of the 13 different chests players currently have to choose from). In fact, the chance of getting at least one epic item from 20 rolls is only around 65%. To work this out, you need to consider the chance of NOT getting an epic item in 20 rolls which is 95% (the chance of not getting an epic item in one roll) to the power of 20. For those wanting a particular general, the chance of getting a specific epic item in 100 rolls is only around 70% – so you could easily spend a whopping £500 and still not get it. This problem has been massively exacerbated by a feature which was introduced later: originally there was no advantage to having more than one copy of the same general but players can now merge multiple copies to promote generals and make them more powerful. Promoting a general to the highest 8 star tier requires a total of 54 copies of the general and the amount that a player would need to spend on chests to collect 54 copies of just one epic general is nothing short of eye popping (especially when you consider that it could be a 9 year old going rogue with a parent’s account!). Some players evidently do spend thousands, as there are 8 star generals on the loose in the game.

Loot Boxes Are Not Just Online

Another thing I noticed in Castle Age was that a lot of players were completely relaxed about the whole concept of the chests and didn’t consider them to be anything controversial, dangerous or even novel.

To understand why that was, we need to look a lot further back into the past. Our first stop is 1993 when Wizards of the Coast released a collectible card game (CCG) called Magic The Gathering. If you’ve not heard of this game, seriously you must have been living under a rock for the last 25 years; as of 2015 it had around 20 million players and tens of billions of Magic cards have been printed. In fact Magic The Gathering was the first CCG. Central to the strategy in the game is building a deck to play with; after buying a basic starter deck players can acquire more and better cards by purchasing booster decks which – as you may have guessed if you didn’t already know – come in a sealed package, with no knowing ahead of time what you will get (although all Magic booster packs contain the same distribution of common and uncommon cards and one rare card, the value of rare cards can vary dramatically).

Clearly anyone who has played Magic The Gathering more than extremely casually will already be comfortable with the concept of loot boxes. Official Magic tournaments, however, run in a variety of formats with regard to which cards are allowed meaning that there is little pressure on players to spend more than they are comfortable with.

Magic The Gathering may have been the first CCG (it was later followed by Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh and many others that are even more mainstream due to associated video games and TV series) but it certainly wasn’t the first set of collectible cards! For that, we have to look even further back in time, all the way to the 19th century when trading cards featuring the sports players of the day first started to be packaged with cigarettes or bubble gum. After the second world war, trading card companies such as Topps started to sell “wax packs” of several cards and although these still contained the bubble gum as well (it wasn’t removed until the 1980s) this was really where the concept of a loot box started to take shape.

While Magic The Gathering (and Castle Age) are mainly played by adults, the Pokemon CCG has child appeal and so do sport trading cards such as Match Attax; in 2009 40% of boys in the UK between 7 and 13 years old were said to be collectors.

I took this picture at a supermarket checkout – and basically, this is a form of loot box, isn’t it? It’s not just sports trading cards either – anyone remember GoGos Crazy Bones? And what about Lego minifigures which are always sold in sealed bags and in 2013 included the super rare Mr Gold figure? And while we’re thinking along these lines, what about Kinder Surprise eggs? Note that I’m not making the same point here as the VP of Electronic Arts did in Parliament back in June – claiming that the resemblance between Kinder Eggs and loot boxes makes loot boxes “quite ethical” – I’m making the argument the opposite way round and suggesting that the entire “mystery box” mechanic is a form of gambling and we shouldn’t be so relaxed about it. So it’s not”Kinder Eggs are OK so there can’t be a problem with loot boxes” but “there’s clearly a problem with loot boxes, maybe it actually starts with Kinder Eggs”!

At least with these children’s toys, it’s harder to go out of control with multiple purchases because they are physical items that you have to go to a shop to buy (or wait to have delivered if you buy online).

Match Attax are completely socially and culturally acceptable and mainstream, right? But should we actually be worried about them, as we are about video game loot boxes? And would we be, if we didn’t already have a such a relaxed attitude, collectively, to another form of gambling? I’m talking about the National Lottery (which is often not considered to be gambling at all by those who play it) and specifically about National Lottery scratchcards, which can be purchased legally by anyone 16 or over from supermarkets, convenience stores, newsagents and petrol stations all over the country. [EDIT: the minimum age was raised to 18 in April 2021].

The Problem With Scratchcards

Buying a ticket to one of the main lottery draws is akin to buying a raffle ticket or prebuy for an online bingo game – you have to wait for the draw to take place to find out if you won anything and let’s face it, almost all of the time you won’t have. This is why it doesn’t feel so much like gambling – it’s more like throwing away some money on a bit of fun (and really, how does that differ from going to the cinema?) Scratchcards, on the other hand, are much more like slot machines and have many of the characteristics of hardcore gambling – in particular, the instant gratification and the ability to carry out a large number of transactions in a short time period. Loot boxes are like this too – the thrill of opening the box is like the thrill of scratching off the card or spinning the slot machine.

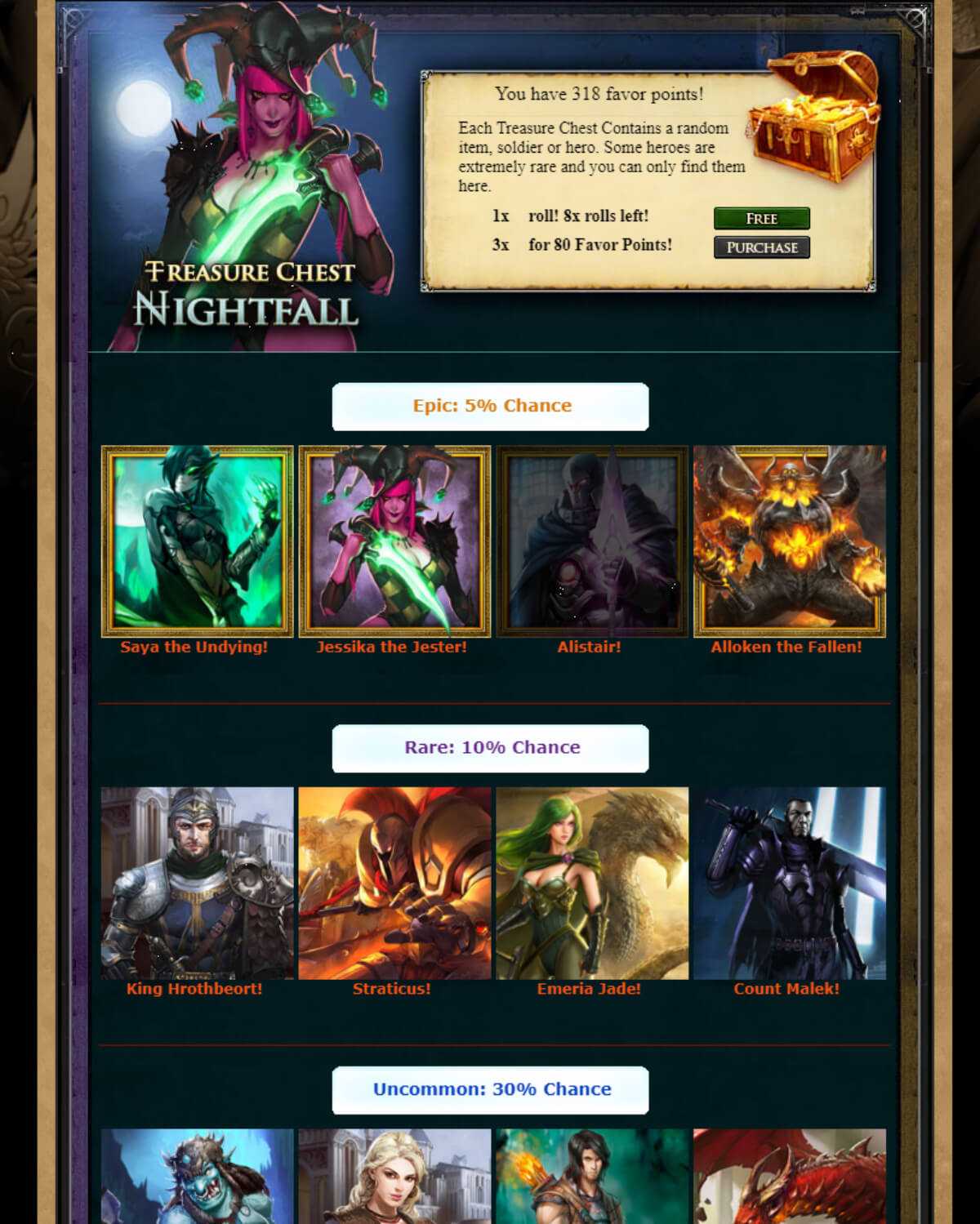

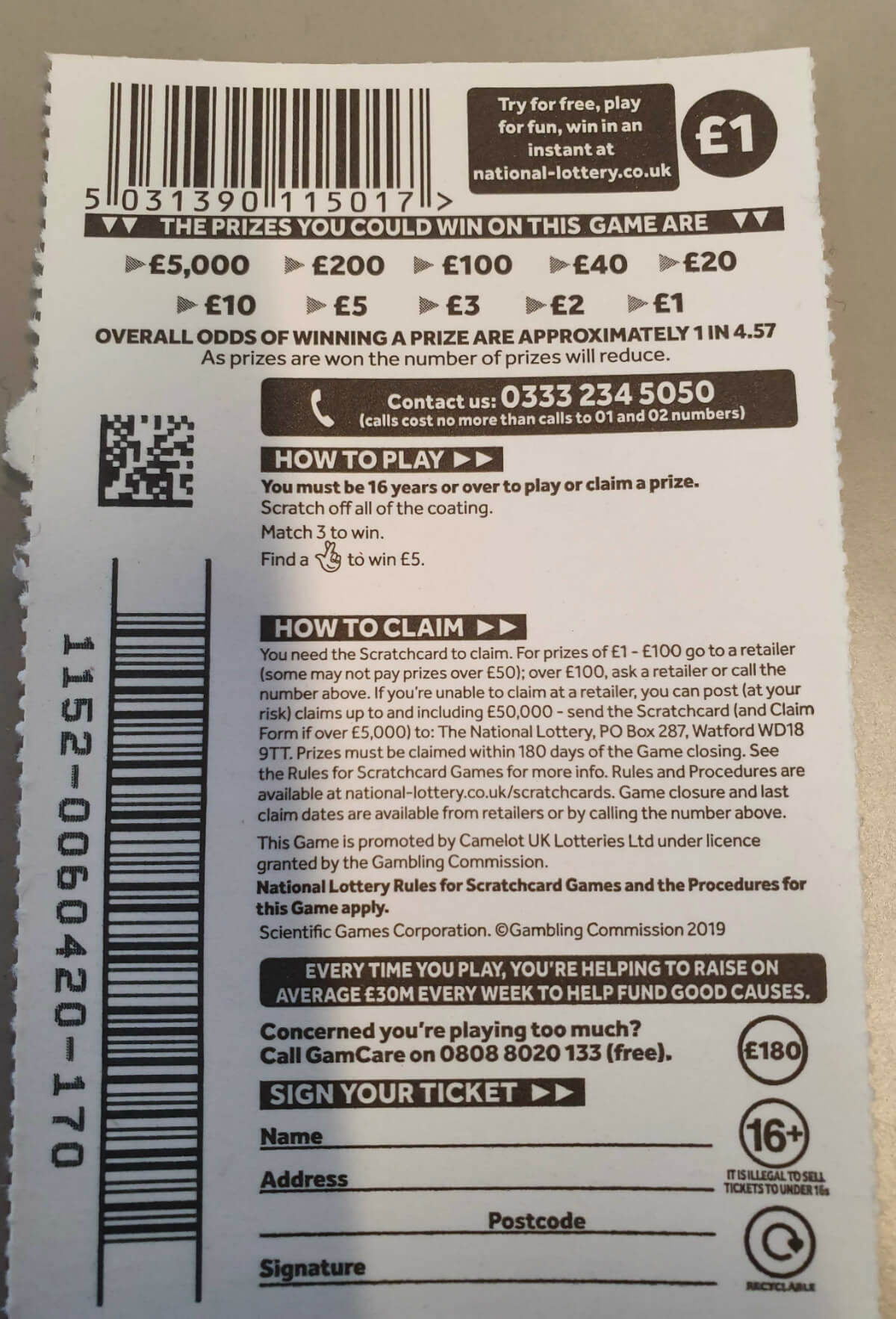

When you buy a scratchcard, all that you are told at the point of sale is what the overall odds of winning a prize of some kind are, what prizes you can win, what the top prize is and sometimes how many top prizes there were when the game was launched. If you go look on the National Lottery website, first you’ll find information on how many top prizes are yet to be won for each type of scratchcard and then – if you dig deeper and don’t mind reading small print on a PDF – information on what the chances of winning each prize are at the start of the game before any cards have been sold.

For example, the Bangers N Cash scratchcard in the picture just says “top prizes of £5000” gives a list of other prizes you could win and states the overall odds of winning a prizes as 1 in 4.57. Visiting the National Lottery current scratchcards page on the day of purchase showed 3 of these prizes still to be won – but in order to find out that there were originally 5 such prizes and the initial chance of winning a £5000 prize was 1 in 2,011,680 it was necessary to click through to the “Game Procedures” PDF.

You would think that people would check on that sort of information BEFORE buying a scratchcard and perhaps they would if the product wasn’t government sanctioned – but in fact, there have been cases of scratchcards continuing to be sold after all major prizes have been claimed (retailers are told not to open any new packs but need not remove any that have already been started from sale).

Now, one need look no further than the Monty Hall problem to see that people in general have an extremely poor grasp of the maths of gambling. It goes like this:

- You are on a TV gameshow where you must choose between three doors.

- Behind two of them are goats and behind the other is the car you want to win.

- You choose one of the three doors. The host (who knows where the car is) opens one of the other two doors to show a goat.

- You are asked whether you want to change your mind and pick the remaining door instead of your original pick. Should you?

Many people persist in the belief that the chances are 50-50 between your original pick and the remaining door even after it has been explained in detail why you have a 2/3 chance of winning the car if you swap and 1/3 if you don’t.

Or try this problem:

- For £10, you can enter a coin-tossing game. The coin has been tested and certified fair. In the game, the coin will be tossed 10 times. If all 10 are heads, you win £100,000. Would you enter?

- What about a game with the same stakes and prizes but where you are betting on 4 rolls of a dice all being 6? Would you enter that?

- Which of the two games is better to enter?

- Would it be better to spend the £10 on 10 scratchcards (with a top prize of £100,000) or 5 lines on a lottery ticket (where you could win millions) than enter either of them?

The answer is that in all three scenarios, you will almost certainly lose your £10 (though perhaps not all of it in the case of the scratchcards) BUT:

- The chance of 10 heads is 1 in 1024 – and since the prize is 10,000 times the stake, the coin tossing game is heavily skewed in the player’s favour with a theoretical RTP (return to player) of over 900%. You would need to play hundreds or thousands of time to come out ahead though, as this game is extremely high variance (very infrequent but very large wins).

- In the 4 rolls of the dice, the chance of 4 sixes is 1 in 1296 – so a bit worse than the coin tossing game, but still heavily skewed in the player’s favour with a theoretical RTP of over 700%.

- The RTP in the lottery (another very high variance game) is not even 70% – but psychologically, many people would feel much more comfortable buying the lottery products repeatedly than playing the coin or dice game even once.

The air of respectability lent to the lottery by its being government backed is undoubtedly a factor here, but also there’s a failure to grasp the maths, or even show any interest in the maths. Even where the odds are clearly stated (as in the Castle Age mystery chests) or ought to be obvious (Monty Hall) people evidently fail to get their heads round the relationship of risk and reward, and this perhaps explains why no-one seems to care much when the odds are NOT clearly stated.

The closest thing lottery scratchcards have to a RTP is the percentage prize money makes up of the total face value of cards printed (not the same as RTP as some cards may end up never going on sale and also there may be a further print run); this is usually between 60% and 70% and can be found on the National Lottery website buried deep in the small print of the scratchcard data PDF (so deep that it may as well be behind a sign saying “Beware of the leopard”) and NOT on the back of the scratchcard itself. But no-one who buys scratchcards seems to be at all bothered about that.

While there can be no concept of Return To Player in Loot Boxes and Match Attax, there can still be a concept of value for money and what players could expect to end up with over a large number of purchases but again, little or no information is available at the point of sale and no-one seems to be bothered. So essentially, the cavalier way people behave with lottery scratchcards also underpins the attitude to loot boxes.

In fact, it has been known for more than 20 years that scratchcards ARE associated with problem gambling behaviour so it should not come as any surprise that loot boxes are too, and one also has to wonder about those 7 – 13 olds who were collecting Match Attax back in 2009 and whether any of them followed what seems like a natural progression to loot boxes, scratchcards and further down the road that eventually leads to a gambling problem.

A natural progression, that is, if you are only paying attention to the thrill and not to the maths! In Match Attax or Pokemon, while you may not get the rare item you want, every item will have at least some value even if it’s just to swap with someone else. In a loot box, many of the items will be either useless or duplicates of something you already have. And with a scratchcard, in the majority of cases you win nothing at all (but that only makes it even more thrilling when you do win something).

Did you know, also, that there are some (offline) gambling games that have no age restrictions at all and can be played by children? These “Category D” gaming machines include coin pushers, penny falls and some crane grabs and the latter two don’t even have to display RTP information. The Category D crane grabs are especially pernicious as they can appear to be a game of skill but contain a compensator mechanism to ensure that they only pay out a certain percentage of the time regardless of how skilful the players are.

You see where I’m going with this, don’t you? Loot boxes are just one facet of a more general problem and banning them isn’t going to make the problem go away.

The Normalisation Of Gambling

That more general problem is this: gambling, and types of behaviour that closely mimic gambling, are currently completely mainstream and socially acceptable but without any proper public understanding of the associated risks or indeed even what is and isn’t gambling!

This has largely been caused by two things:

- The National Lottery. This let gambling out of the betting shops and racecourses, on to the TV screens and the shop counters. Buying a ticket and watching the draw live on TV became a fun family activity and you could (and still can) pick up scratchcards when you paid for your groceries or petrol.

- The Gambling Act 2005. This enabled operators to advertise a full range of gambling products on TV and radio (previously only the National Lottery, bingo halls and football pools were allowed). In 2012, according to Ofcom, there were 1.39 MILLION showings of gambling adverts on UK television making up 4.1% of all TV advertising spots.

For children and teenagers today, gambling occupies the same space culturally as smoking did when I was young. Lots and lots of us took up smoking in those day because we didn’t understand how dangerous it was (and still is). Now the thing is, we DID know by then of the link between smoking and cancer (and we always knew that cigarettes are a fire risk), but knowing and understanding are not the same thing. Cigarettes were everywhere – in films, on television, in advertisements, in every public place, on the Underground, totally ingrained in our culture and trivialising and normalising smoking – and the message this conveyed was completely at odds with the health and safety warnings.

Since then, many pieces of legislation have been enacted that have systematically marginalised smoking and smokers. Punitive taxation, a ban on advertising and sports sponsorship, increasingly in-your-face health warnings on cigarette packs, increasingly graphic and scary anti-smoking advertising campaigns and the banning of smoking from enclosed public spaces and workplaces have all turned smoking from a mainstream activity to a fringe activity.

In the years since I started writing about bingo and slots back in 2013, I’ve seen the gambling industry start to travel down the road to marginalisation with curbs on that massive amount of TV advertising, the tightening of age gating, social responsibility rules , controls on autoplay and the reduction of the maximum stake on FOBTs to £2. But all these measures only address the Gambling Act 2005 part of the problem. The lottery part of the problem is never going to go away, as it would be catastrophic for the good causes it supports if it did. It has been watered down, but only very slightly – the main draws are no longer televised (but are still broadcast on YouTube) and the £10 price point for scratchcards has been discontinued. But right now (December 2019), scratchcards themed on Monopoly and Christmas Advent Calendar 2019 are on sale for £5 each in full view of children and you can even have them delivered with your Tesco online grocery order! Although there is a CAP consultation in place for tightening up the rules on lottery advertising so that no ads or marketing communications that include any reference to scratchcards can feature anyone who is or looks under 25 in any significant role, this doesn’t address child appeal at the point of sale.

As long as we have the lottery, gambling can never be pushed as far to the fringes as smoking has been, and rightly so. What really marginalised smoking in the end was the ban on smoking in workplaces and public indoor spaces and that was driven by the harmfulness of secondhand smoke to everyone in the vicinity. Although gambling related harm to others is a serious concern, the mere act of gambling doesn’t cause automatic damage to bystanders so there should be no need for quite such draconian measures.

The mixed messaging, though, seriously needs to be addressed. How can someone truly understand that splurging on loot boxes or online slots is dangerous if at the same time they are being sold Government backed scratchcards as if they were candy? If it’s not addressed, we could be facing a huge demographic time bomb in the form of a generation of problem gamblers.

Ban? Or Educate & Regulate?

In the great scheme of things, blanket bans are rarely effective – just look at what happened with Prohibition in the USA (a blanket ban on alcohol). Basically, Prohibition drove drinking underground, problem drinkers still drank, the drink industry was gifted into the hands of organised crime and the government lost out on a lot of tax revenue. Regulation, on the other hand (as has been done with smoking) does work – people can still smoke if they want to and the government still gets all the tax.

Besides, if you ban loot boxes, where do you draw the line? Do you ban everything with a mystery box type mechanic including Magic the Gathering, Pokemon, Match Attax, Lego minifigures and even Kinder Eggs? How ridiculous would that be while scratchcards remain on sale?

In the case of all of these toys and games that include a gambling like element, the thrill of the gamble is peripheral to the entertainment inherent in playing the game, collecting the cards, playing with the toys – whereas with the scratchcards the thrill of the gamble is the entire point. If the gambling like elements in these toys and games are softening people up for real money gambling, the people who are at risk of developing a problem ought to be identifiable long before they get as far as trying scratchcards and for everyone else, there’s a valuable learning opportunity about the maths of gambling!

In UK schools there is a curriculum element called PSHE (Personal, Social and Health Education) which is supposed to cover moral, social and cultural issues and give children the knowledge, skills and understanding they need to lead confident, healthy and independent lives. Shockingly, as yet there is no statutory requirement for PSHE to cover the dangers of gambling but the PSHE Association has made a great start with a set of curriculum resources aimed at year 10 (14-15 year olds) [UPDATE: from September 2020 gambling issues including addiction and cumulative debt WILL be a compulsory part of the PSHE curriculum in secondary schools] .

This is an excellent time to start talking about the dangers of real money gambling – not too early but well before they can buy scratchcards legally at age 16 – but way too late to start talking about loot boxes as by age 14, that horse has well and truly bolted. The organisation YGAM which aims to educate and safeguard young people against problematic gambling and gaming recognises this: they run workshops for educators working with children as young as 7.

As a parent, what I would like to see is education for everyone (not just children who already have some kind of problem) about loot boxes in all their various guises much earlier on – as part of primary PSHE and part of primary maths – and yes, that includes Kinder Eggs! For example, Kinder Egg toys come in sets which children like to collect – so how many eggs do they think will be needed to complete a set of 10 toys? (Clue – it turns out the maths of Kinder Eggs is surprisingly complex but it’s a lot more than you might think, close to 30). This could be taught by real world experimentation, not by opening dozens of Kinder Eggs, but by drawing counters out of a bag until you have all 10 colours.

The maths of all the other mystery box toys and games needs to be taught too, because one of the things that causes loot boxes to be a problem is that when a young person who has already experienced all the other mystery box type toys moves on to video game loot boxes, they have a false expectation as to what they are going to get. This is because not only have they not grasped the probabilities in the first place, they haven’t noticed that the probabilities get worse as you move online (and worse again for scratchcards, of course).

Unfortunately there is a big problem with this because – as I mentioned earlier – in the case of video game loot boxes the odds are very rarely published. The tide is turning, though, as many video game companies have agreed to loot box odds disclosure by the end of 2020.

Match Attax do publish the probabilities – sort of. In small print on the back of each packet is a guide to how rare various types of card are expressed as “1 in X packs has this type of card” as can be seen in this video where a collector opens some packs to see if that matches his experience. So in a way, collecting Match Attax can help youngsters understand the maths of gambling as long as they also understand that in other types of loot boxes the probabilities may be different (and worse).

Loot box odds disclosure is bound to help with that understanding, as long as it is plainly stated and not buried too deeply in the small print. By disclosing the odds voluntarily, the video game companies presumably hope to avoid a ban on loot boxes or other forms of excessively restrictive regulation. What are the chances of them doing it consistently and properly, though, without some form of regulatory oversight? What few seem able to agree on is the detail of that regulatory oversight, but as multiple possibilites are now being discussed, regulation is almost certainly coming.

How To Regulate?

Regulation by the Gambling Commission (as the children’s commissioner suggested) is one possibility but would this really be appropriate? Although loot boxes introduce a gambling like element to the games in which they feature, this is far from being the main purpose of the game and there’s no real money return. In that sense (but only in that sense) loot boxes do indeed resemble Kinder Eggs more than they do scratchcards. There’s also the argument that classifying loot boxes with real money gambling makes it more likely that players WILL progress from one to the other.

The rationale for the Gambling Commission getting involved would be to impose a requirement not only for the odds to be disclosed (which arguably ought to be covered by general consumer law about how products are advertised anyway) but for them to be independently verified by testing – as happens with real money gambling games, but not with Match Attax or any other form of mystery box purchase.

While there has also been talk of maximum daily spend limits and of age restrictions, I would argue that this is not necessarily a matter for the Gambling Commission either. The video games industry already has its own age rating system, PEGI, which covers the suitability of content in general (e.g. violence, adult themes) not just loot boxes. PEGI covers depictions of gambling – if the game shows a casino it has to be PEGI 12, 16 or 18 – but although there is a content descriptor for in-game purchases it isn’t currently associated with any specific PEGI rating. Now clearly, simply age gating all games with in-game purchases isn’t feasible as it would result in freemium games like Candy Crush Soda Saga which has completely innocuous content being classed as a 14, 16 or 18 alongside games with violent or otherwise adult content, destroying the distinction between them. These freemium games make all their revenue from in-game purchases of power ups and so forth and although they do sometimes include spin the wheel type bonus games, they are usually free to play. So maybe PEGI could make more of the difference between loot boxes and other types of in-game purchase? Possibilities might include:

- Classing loot boxes as gambling related content requiring PEGI 12 or higher

- Classing loot boxes as adult content unless there is a facility to disable them or set a maximum spend limit

As it happens, most of the well known loot box games ARE at least a PEGI 12 due to violent content and a high profile game that isn’t, Rocket League, has just got rid of loot boxes entirely; they still have in game purchases but now you know exactly what you are getting! There’s another very high profile game, though, that still has loot boxes – FIFA, which is PEGI 3. From FIFA 19 onwards, they have been publishing the odds, but their loot boxes remain very popular.

PEGI 3 means “suitable for children”; it does not mean “ONLY suitable for children”and FIFA players are all ages. So suddenly, we’re back to a Match Attax like situation again and not just because both games are about football – many Match Attax collectors are adults. Now, there are no age restrictions and maximum spend limits on Match Attax and no-one would seriously suggest that any are needed – because in the case of the non adult players like the 7 – 13 year olds we talked about earlier, their parents (or other responsible adults) are in control of how much pocket money they get and are aware of what they are spending it on! To help them do the same for video games, PEGI has pages of advice about parental controls including specific instructions on how to restrict or disable in-game purchases on all the various gaming platforms and how to restrict a device’s access to games based on their age rating.

As for a maximum spend limit, that too can be set by parents (well, sort of) even if there’s no facility to restrict or disable loot box purchases in the game (I agree that there ought to be, though). A prepaid debit card or gift card, with no more forthcoming when it’s used up, is a way of achieving this.

I personally believe that it is better to give a young person the opportunity to waste their own money on loot boxes under controlled conditions – once they are mature enough to come to understand through experience that they are indeed wasting their money – rather than ban them completely. It has to be their own money, though, for there to be a meaningful choice between spending it on a loot box or spending it on something else. Far better to learn that lesson early (at home and at school) in connection with loot boxes or other mystery box type purchases than learn it later and far more dangerously and painfully with scratchcards or any other form of real money gambling!

What Else Can Parents Do?

It’s not just about what you say to your children about loot boxes, scratchcards or any other form of gambling type behaviour, it’s about what you do with or in front of them. One very important thing you can do is ensure that you DON’T trivialise gambling (whether or not it involves real money). When a parent buys a lottery ticket for their child to check the numbers against the live draw, or buys them a scratchcard to scratch off, it may seem like a harmless piece of fun – but in fact, the child is being exposed to the rewards of gambling without any of the associated risks and when you put it like that, it’s not hard to see that it is potentially harmful – especially if the child is not mature enough to understand fully how money works. What’s more, the same holds if the parent buys a loot box for their child or lets the child charge a loot box to their credit card – again, the child is not taking the risk but is experiencing the thrill of opening the box. Regulation and age gating can help to keep gambling type behaviour away from children who are too young to understand it but parents must also behave responsibly – you wouldn’t give your 5 year old a gin and tonic, so don’t let them buy loot boxes on your iPad!

At Best New Bingo Sites all of our reviews are completely honest and written by industry experts. We aim to present all our offers as transparently as possible with a full explanation of the terms and conditions. We receive commission from the sites we feature and this may affect how prominently they appear on our site and their position in our listings.